Listen to an audio file of this resource.

Introduction

From the time your child is born, you create enriching opportunities where your child can

- explore,

- learn,

- develop new skills,

- create, and

- thrive.

You see your child develop and change in extraordinary ways. You know their developing brain continues to mature as a teen. In fact, during the teen years, your child’s brain goes through dramatic changes, second only to the first three years of life!1 This makes the teenage years particularly vulnerable to negative impacts on the brain. Between the ages of 12 and 21, alcohol use can significantly harm the brain.1 Drinking alcohol in the teen years can result in negative changes to brain development and function. Let’s explore

- the consequences of underage drinking,

- the impact of alcohol on the developing teenage brain, and

- your role in delaying the use of alcohol.

Most Montana parents (91%) DISAPPROVE of high school students drinking alcohol.2

Brain Science Made Easy

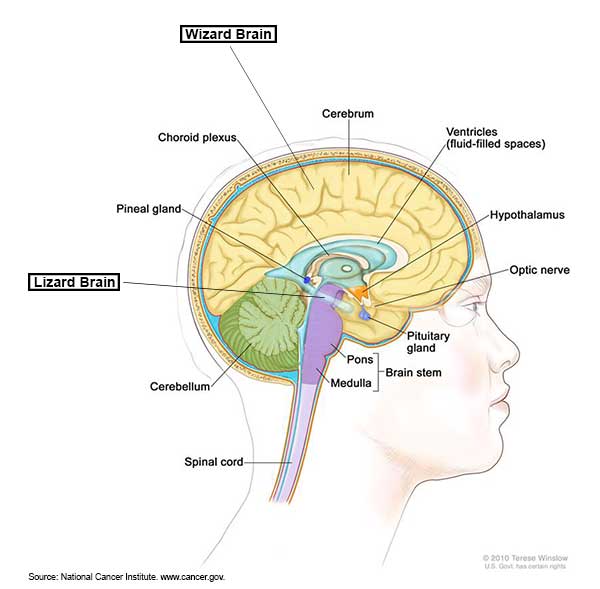

There are two primary parts of the human brain: the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex. The limbic system is responsible for, among other things, our

- emotions (fear, anger, negativity),

- quick decisions (fight or flight),

- social needs, and

- reward.

The limbic system is a reactionary system and can be called the lizard brain because it is the most primitive part of the brain and is comparable to the entire brain of a lizard. It is fight or flight, but not a lot of thought. It tells your teen to jump out of the way of a runaway bus when there is little time to think about it.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for

- decision making,

- thinking through consequences, and

- controlling impulses.

The prefrontal cortex can be called the wizard brain. It is the thinker. When the wizard brain is in charge, your teen will stop and think things through and consider consequences.

The lizard brain processes all stimulus received from a situation and communicates with the wizard brain through a relay system. During the teen years, both the lizard brain and wizard brain go through massive changes and development to create more efficient systems.3 The lizard brain is done with this restructuring around the age of 15, but the wizard brain is not done restructuring and maturing until the mid-twenties. Therefore, in times of stress or social pressure, the teen brain is dominated by the lizard brain – the need for reward and meeting social needs. Rational decision making and considering consequences (the wizard) take a back seat.3

This disconnect between the lizard brain and the wizard brain is made worse by alcohol. Alcohol use can disrupt healthy brain development and slow the development of the wizard brain, thereby increasing the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors.

Even though a teen may know about the risk of drinking alcohol, in certain situations, they may still choose to drink. “I just wasn’t thinking” is partially true because of their developing brains.4 Because teens are very “now” oriented, whatever immediate situation a teen is in at that moment has a significant impact on their decision making.

As a parent or someone in a parenting role, you have probably already had multiple conversations about the harmful consequences of choosing to drink alcohol or try other drugs. And, you may have ended those conversations feeling confident that your teen understands the risks. However, all the brain matter required to apply their knowledge at the right time may not be there – the wizard may still be sitting in the back seat instead of the driver seat.5

The way to support your teen’s brain is to prepare your teen for high-risk situations that they will encounter by continuing to have frequent conversations about alcohol. Teens need the structure and support of their parents or those in a parenting role to help prepare their brains to make the right decision when the pressure is high.

Impact of Alcohol on the Brain

Alcohol has a greater negative impact on a teen’s brain than on an adult’s brain. This is because during the teen years, the brain is going through significant structural and functional changes. Neural connections that are used frequently are being strengthened while those that are not used are weakened or discarded.

When alcohol is used during this time that the brain is going through a clean-up and pruning process, it affects the developing brain in several different ways.

- It affects the way neurons communicate with each other.

- It damages brain tissue.

- It impacts areas in the brain focused on learning and memory.6

Neurons communicate with each other using chemicals called neurotransmitters. Two neurotransmitters that are particularly impacted by alcohol use are dopamine and GABA. Dopamine is involved in motivation, learning, and reward. GABA is involved in mood management and has a calming, sedative effect. Alcohol disrupts these neurotransmitters making it more difficult for teens to

- learn new behaviors,

- feel motivated,

- calm their emotions, and

- feel rewarded.7

Alcohol also damages brain tissue in a few key parts of the brain. In particular, alcohol has a negative impact on the hippocampus, which is necessary to form new memories.6

Alcohol also affects the white and gray matter of the brain. White matter acts as the superhighway and connects information across the brain.6 When white matter is damaged by alcohol, it makes it harder to control behavior. Alcohol also damages gray matter, which is responsible for processing information in the prefrontal cortex thereby affecting

- attention,

- concentration, and

- decision making.6

The teen years are an important time for the developing brain. Alcohol can negatively impact this developmental process.

Can Parents and Those in a Parenting Role Really Make a Difference?

As a parent or someone in a parenting role, you are the most important influence in your child’s life.8 You play an essential role in your child’s decision not to drink alcohol.9 Being actively involved in your child’s life makes it less likely that they will drink alcohol.

You have a direct impact on whether your child decides to drink alcohol when you

- talk with your child about alcohol and its negative impacts,

- model healthy and positive behavior, and

- stay involved in their life.

The age at which a child drinks matters in terms of the negative effects of alcohol. You can greatly reduce repercussions of alcohol on your teen’s brain development if you can delay the age at which your teen initiates alcohol use.10

Teens who learn about the risks of drug use from their parents are less likely to use drugs than those who don’t.11

Teens desire the approval of their parents and those in a parenting role. Two-thirds of youth ages 13 to 17 say that losing their parents’ respect is one of the main reasons they don’t use drugs.11

Teens who feel closely connected to their parents are less likely to use alcohol.11

Youth who begin drinking before age 15 are four times more likely to develop future alcohol dependence compared to youth who begin drinking after age 21.12

Closing

The teen brain is more susceptible to the negative effects of alcohol than an adult brain over the age of 25. Alcohol use as a teen can result in significant impairment in the

- development,

- structure, and

- function of the brain.

Because of how the human brain develops, when teens use alcohol it puts them at an even greater risk for engaging in other risky behaviors like initiation of other drugs and teen pregnancy.12 Longer-term consequences include permanent learning disabilities and greater likelihood of misusing alcohol later in life.12

Unfortunately, despite being such an important influence, parents and those in a parenting role often underestimate the influence they have on their teen’s decision to drink alcohol. Parents and those in a parenting role underestimate the difference they can make in guiding their teen’s choices and behaviors. You make a difference.

Connect with other Montana parents and those in a parenting role about underage drinking and drugs at LetsFaceItMt.com.

Download and print the at-a-glance resource highlighting key information for Underage Drinking.

References

[1]Giedd, J.N., Blumenthal, N.O., Jeffries, et al. (2010). Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience, 2 no. 10 (1999): 861-3.

[2] Center for Health and Safety Culture. (2018). 2017 Montana Parent Survey Key Findings Report, Bozeman, MT: Montana State University.

[3] Strauch, B. (2003). The primal teen: what the new discoveries about the teenage brain tell us about our kids. Anchor Books: New York.

[4] Baxter, L., Bylund, C., Imes, R., & Routsong, T. (2009). Parent-child perceptions of parental behavioral control through rule-setting for risky health choices during adolescence. Journal of Family Communications, 9, 251-271.

[5] American Medical Association. (2009). Harmful consequences of alcohol use on the brains of children, adolescents, and college students. American Medical Association.

[6] Monti, P. M., Miranda Jr, R., Nixon, K., Sher, K. J., Swartzwelder, H. S., Tapert, S. F., … & Crews, F. T. (2005). Adolescence: booze, brains, and behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(2), 207-220.

[7] Clark, T., Nguyen, A., Belgrave F., & Tademy, R. (2011). Understanding the dimensions of parental influence on alcohol use and alcohol refusal efficacy among African American adolescents. Social Worker Research, 35(3), 147-157.

[8] Habib, C., Santoro, J., Kremer, P., Toumbourou, J., Leslie, E., & Williams, J. (2010). The importance of family management, closeness with father and family structure in early adolescent alcohol use. Addiction, 105, 1750 -1758.

[9] Grant, B.F., and Dawson, D.A. (1998). Age at onset of drug use and its association with DSM–IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse 10:163–173, PMID: 9854701.

[10] The U.S. Department of Education, The Drug Enforcement Administration. (2014). Growing Up Drug Free: A Parent’s Guide to Prevention. Justice.Gov. http://www.justice.gov/dea/pr/multimedia-library/publications/growing-up-drug-free.pdf.

[11] National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2004). Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking, Richard J. Bonnie and Mary Ellen O’Connell, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

[12] American Medical Association. (2009). Harmful consequences of alcohol use on the brains of children, adolescents, and college students. American Medical Association.

Recommended Citation: Center for Health and Safety Culture. (2018). Alcohol and the Teenage Brain. Retrieved from https://parentingmontana.org.